Shades of co-design

But is it co-design? People so often ask. Sometimes with a hint of embarrassment or frustration. The thing their colleague or client is calling “co-design” seems so far removed from what they (often rightly) assume I would consider actual co-design.

I used to be pretty hardline about this. So much so that I gained the nickname of Co-Design Cop in one workplace. I still cringe at that label. But I have tried to build a shared definition of co-design, most obviously in my 2018 article on co-design for policy.

I share Jo Szczepanka’s concerns about the amount of ‘faux design’ out there. I also encourage people to take the But is it co-design? quiz. KA McKercher had heard that question so many times that they created this neat little tool to guide us through the characteristics of this unique approach to public and social innovation.

These days, I’m less certain that we all need to share the same definition. I take heed of calls to embrace plurality and respect local traditions, adapting to place/context, and avoiding imposing ‘universal’ models in colonial ways.

I still think it’s important to get clear on what you mean when you say “co-design”. We need to be coherent and consistent in order to communicate effectively (while allowing some flexibility and adaptation). It’s helpful for a team to agree on the approach they're taking. Otherwise, you might all be rowing in different directions. That doesn't mean we need one universal, overarching definition of co-design that can apply to every project, sector, issue or country at any time.

There are many forms that co-design can take, and still stay true to its roots:

— valuing local knowledges;

— seeing everyone as the expert of their own lives; and

— offering appropriate spaces, scaffolding and invitations for people to tap into their creativity and work constructively across diversity.

What that looks like will depend on the scale and scope of the initiative, the resources and capabilities available, and the enabling and authorising conditions. In some contexts, it is not reasonable to expect a full-blown co-design process with shared decision-making and generative methods from start to finish.

I’ve witnessed so many people struggling to lead and implement co-design activities in low-resource settings and hostile environments. Then some beat themselves up for not fully achieving the ideal process and outcomes they’re aspiring for. If that sounds familiar, I'm writing this piece to reassure you that you are not alone. And to encourage us to take a more nuanced, context-responsive approach to defining co-design.

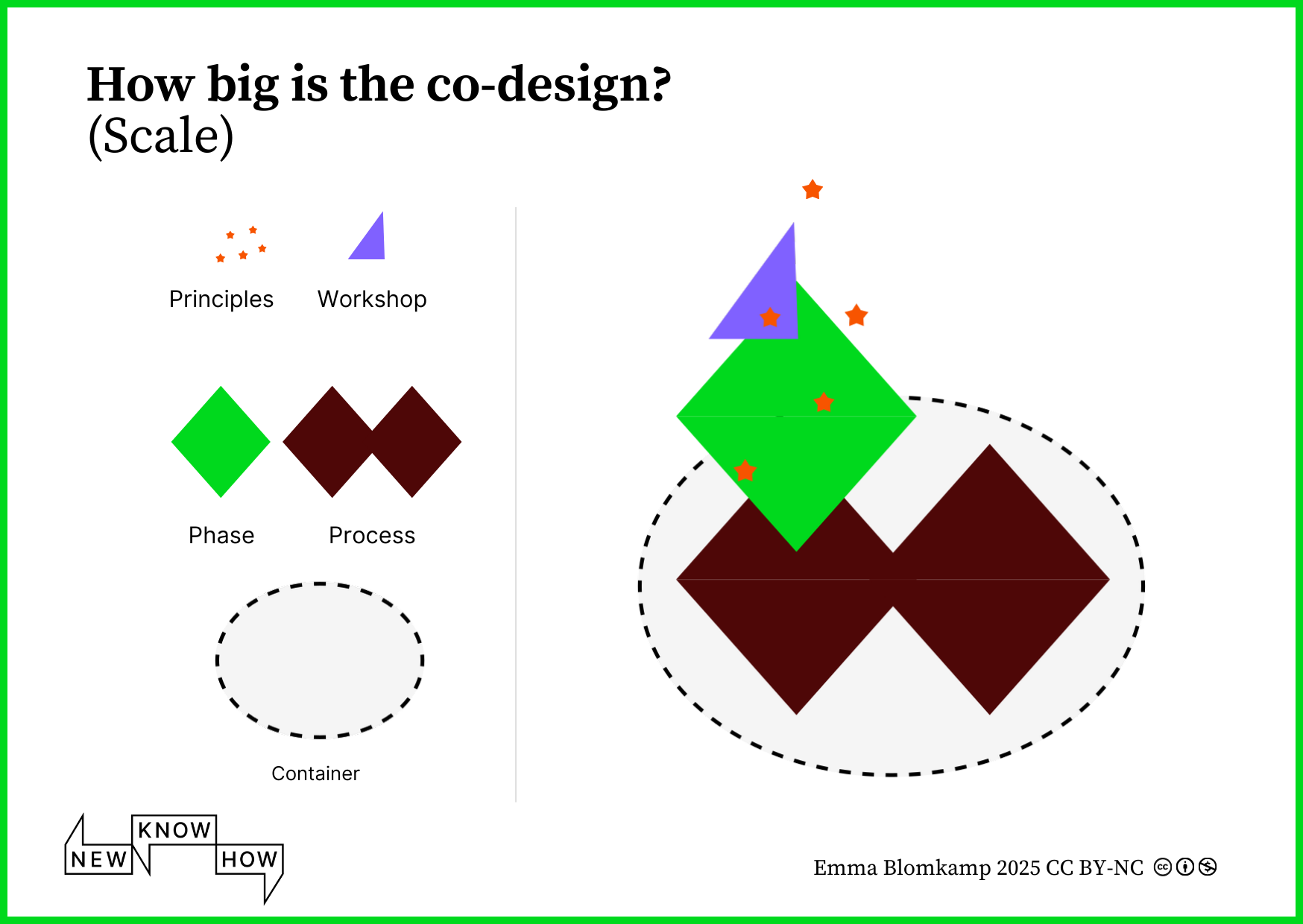

You might even think about this, with tongue in cheek, as 50 Shades of Co-Design. Many people are familiar with a ladder or spectrum of participation, which we might visualise as a vertical axis. This answers the question, how much ‘co’? On the horizontal axis, I'd suggest we consider how much ‘design’ is involved. Another sort of axis is the scale of co-design, starting with a sprinkling of co-design principles, all the way through to a full co-design container, such as a participatory and innovative organisation that enables co-design at every level.

This is all getting a bit much for a single 2-D matrix, so I’ll elaborate on these three lenses and include a separate visual representation for each below. I’m pulling together work from a variety of sources, so I’ve included a reference list too.

One final lens you might apply—not illustrated below—is whether it's an internal or external process. True believers often shy away from calling something co-design if it has only involved staff from within an organisation. But there might be cases where that's sufficient. You might be designing a new workflow. If your team has all the knowledge and skills needed to identify what hasn't been working, what could be improved, and how to implement it, that could be an internal co-design project. On the other hand, if you're designing healthcare without patient involvement or educational programs without students participating, it's not really co-design unless it's an external process, involving people from outside the organisation too.

Three lenses to identify various shades of co-design

A. Scale: How big is the co-design?

Co-design principles are sprinkled throughout the work. For example, meetings are held in more creative or participatory ways, and lived experience is centred when analysing research outputs.

There is a co-design workshop or some sort of creative and participatory session(s) that involves key people affected by the issue.

A phase involves co-design. Some stages of the work (e.g. research or implementation) may take a different approach. Still, there is a co-design phase within the broader process, where a range of people with lived and professional experience actively contribute knowledge and ideas, and help make decisions about how to proceed.

The whole process takes a co-design approach. From start to finish, creative and participatory methods are used to build shared understanding and take action. There is a core and consistent co-design team driving the process, made up of a mix of people with relevant lived and professional expertise, with appropriate facilitation, creative support and care.

The container is co-designerly. An evolutionary organisation or cooperative network shares decision-making and enables innovation—embedding co-design in everyday activities and governance structures—so that the process is co-designed too.

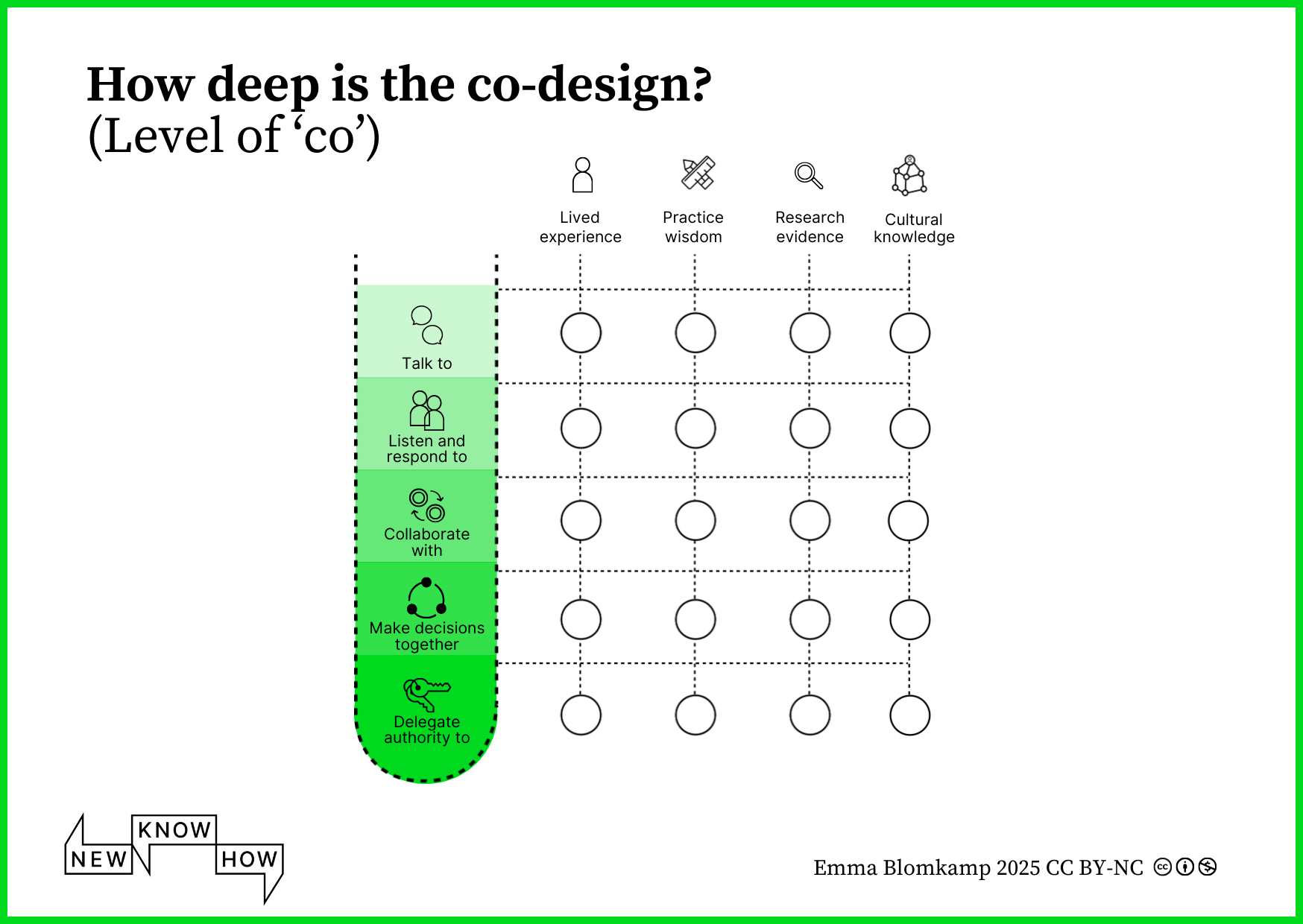

B. Level of ‘co’: How deep is the co-design?

I imagine this as a ‘well’ of participation, building on Arnstein’s (1969) ladder of participation and the IAP2 spectrum of public participation. This includes but extends on the three kinds of expertise articulated by TACSI (2020) and innovate change (where I worked, 2013-16).

Some ‘ways of knowing’ often integrated in co-design are:

— lived or living experience (e.g. someone directly affected by the issue in their personal life)

— practice wisdom (e.g. someone with professional experience in the area)

— research evidence (e.g. a specialist or academic expert in the field), and

— cultural knowledge (e.g. an Indigenous knowledge-holder or Traditional Knowledge Keeper who has been taught by an Elder or a senior knowledge keeper within their community).

Starting at the top, we can consider the depth at which each of these types of expertise is integrated into a design project or innovation initiative:

Talk to: relevant people* are consulted and may be invited to provide feedback on results, options and/or decisions (e.g. via a survey or email).

Listen and respond to: relevant people are included and listened to actively at key moments to ensure that their concerns and aspirations are understood and considered (e.g. in interviews, meetings, committees).

Collaborate with: relevant people are active partners in developing ideas, assessing options and making recommendations (e.g. series of inclusive workshops with a co-design team).

Make decisions together: relevant people are involved in making decisions, with shared responsibilities and accountabilities (e.g. a co-design team follows a consent-based decision-making process at key moments).

Delegate authority to: relevant people make the final decision; there is a public commitment to implement what they decide (e.g. a citizen’s jury commissioned by Parliament).

*“Relevant people” here refers to the type of expertise held being pertinent to the issue or project (lived, professional, research, cultural).

If we are not involving all the above types of expertise, with at least some collaboration, I wouldn’t call something “co-design”.

There is not an inherently “good” or “bad” end of this spectrum. The depth of “co” should reflect the context, objectives, scope and principles of the initiative. Not everything can or should be delegated.

I no longer include “devolve” on this scale. I previously defined devolution as where relevant people have the resources and authority to lead the process and implement decisions however they choose (e.g. a community controlled organisation or community-managed program). This is an important structure for community-led action, but it does not necessarily involve co-design.

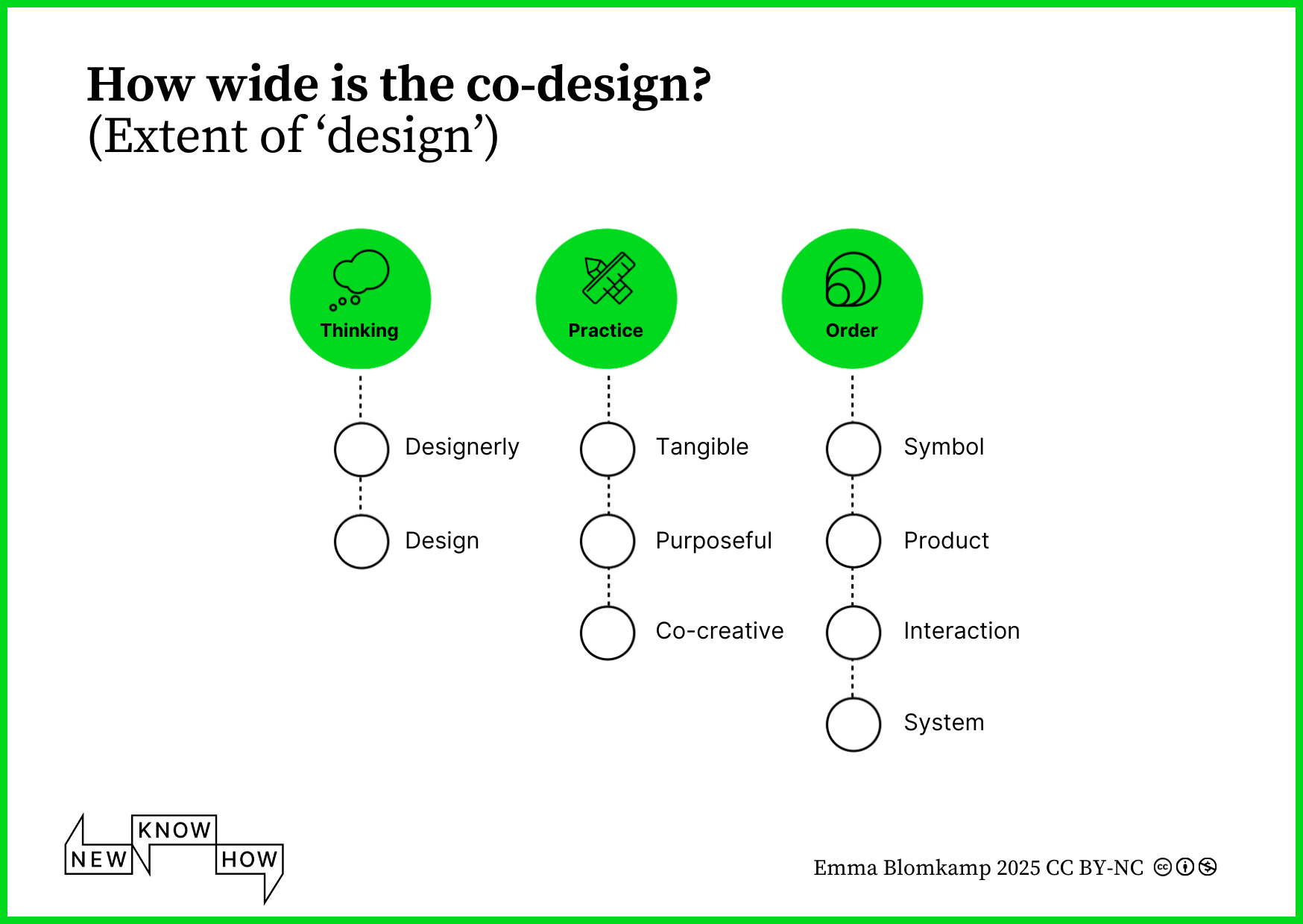

C. Extent of ‘design’: How wide is the co-design?

I consider three different dimensions of design here: thinking, practice and order (another way to think about scale).

There are two main ways we can understand design thinking (based on Cross, Bijl-Brouwer and Malcolm, and Laursen and Haase):

Design thinking—iterative phases of an innovation process; incorporating empathy, creativity and rationality.

Designerly thinking—abductive reasoning, where understanding of the ‘problem’ and ‘solution’ co-evolve, shared understanding is created by oscillating between what is being designed and the larger system, and relevant features emerge as tentative concepts.

Here we identify three key characteristics of design practice, which helps to distinguish co-design from similar but distinct practices of participatory research, community engagement or consultation and co-production (based on, among others: Sanders and Stappers, Cross, and Karpen et al.):

Tangible—using physical materials or visual representations to express ideas, knowledge or stories in external, tangible and tactile ways (e.g. blocks, clay, cardboard, natural materials, physical models, diagrams, illustrations, maps); often creating experiences or evoking the senses.

Purposeful—aiming to address a particular problem or opportunity, to create better results; guided by goals and abilities of potential users or beneficiaries; imaginative and creative action that is constrained by reality.

Co-creative—methods that empower all kinds of people to generate ideas and explore insights and alternatives, emphasising active and creative participation (e.g. sketching, prototyping, cards sorts, scenario building and mapping); sometimes called ‘generative’.

Finally, as in my systemic co-design practice framework, I draw on Buchanan and Jones’s conceptualisations of the ‘orders’ of design as:

Symbol—Symbolic, graphic, visual communications (e.g. a logo or diagram)

Product—Artefacts and material objects (e.g. a chair or keyboard)

Interaction—Activities, experiences and organised services (e.g. a waiting room or intake process)

System—Complex systems and environments (e.g. an organisation, network or public policy)

It’s worth noting, in this era of ecological crises, that Marlieke Kieboom adds a fifth order—life on Earth—to draw attention to the natural order we all operate within. It’s also possible to see ecosystems as part of the fourth order described above.

Asking ‘how much’ rather than ‘what’ is co-design

These lenses are all different ways of asking: how much co-design is there? I hope they offer a more nuanced response to the question, “but is it co-design?”, finding a balance between purism and pragmatism.

There are more and less “co-designerly” ways of doing things. You might be able to dial up co-design more in one part of the process than another. Sometimes a decision has been made in advance, but there are still things that can be co-designed and co-decided within the design, development or even implementation process.

-

This article is a lightly updated version of the blog initially published on emmablomkamp.com on 13 March 2024 and on Medium on 16 April 2024.

Thanks to: Zenaida Beatson, Emma Kaniuk and Georgi Lewis for their contributions to visual design: Alli Edwards for a conversation on the “design” bit of co-design; KA McKercher and the Traditional Owners whose feedback helped to improve the “how deep” lens; and all my clients and participants who’ve encouraged me to refine my thinking on this!

-

Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation,” Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 216-224.

Bijl-Brouwer, Mieke van der, and Bridget Malcolm. 2020. “Systemic Design Principles in Social Innovation: A Study of Expert Practices and Design Rationales.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 6 (3): 386–407.

Blomkamp, Emma. 2018. “The Promise of Co-Design for Public Policy.” Australian Journal of Public Administration.

Blomkamp, Emma. 2021. “Systemic design practice for participatory policymaking.” Policy Design and Practice.

Buchanan, Richard. 1992. “Wicked problems in design thinking”. Design Issues 8:2.

Cross, Nigel. 2023. Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work.

International Association for Public Participation. 2018. “IAP2 Public Participation Spectrum.”

Jones, Peter. 2014. “Systemic Design Principles for Complex Social Systems.” In Social Systems and Design, edited by Gary Metcalf, 1:91–128. Translational Systems Science Series. Verlag: Springer.

Karpen, Ingo, et al. 2017. “A multilevel consideration of service design conditions: Towards a portfolio of organisational capabilities, interactive practices and individual abilities”. Journal of Service Theory and Practice.

Katterl. Simon. 2023. “Co-design or Faux-design? A chat with Jo Szczepanska.”

Kieboom, Marlieke. 2023. “Shapeshifting Design: Imagining an intersystemic space for public service transformation.” Medium.

Leurs, B. & I. Roberts. 2018. Playbook for Innovation Learning. Nesta.

Laursen, Linda Nhu, and Louise Møller Haase. 2019. “The Shortcomings of Design Thinking when Compared to Designerly Thinking.” The Design Journal.

McKercher, KA. 2020.Beyond Sticky Notes: doing co-design for real.

Sanders, Elizabeth B. N. & Pieter Jan Stappers. 2013. Convivial Toolbox — Generative Research for the Front End of Design.

TACSI. 2020. “Co-design Capability Building: Creating Partnerships for Potential - A Peer to Peer Initiative.”

Free resource

Use the Shades of Co-Design worksheet to reflect on how much co-design there is in your project.