What is co-design?

Understanding the process, principles and practice

Co-design has become an increasingly popular approach in public services, health and social sciences, and community development. But what exactly is it? How does it differ from similar concepts? And when should we use it?

Defining co-design

There are several ways to understand co-design, ranging from simple to more academic explanations.

At its simplest, co-design is people making stuff together. This straightforward definition captures the collaborative and generative essence of the approach. It also acknowledges that First Nations communities have been engaged in co-design since time immemorial, long before whitefellas started using this term.

You can also break it down into the ‘co’ and the ‘design’. The co- most often signifies collaborative, though some understand it as collective, community, or co-operative (the original term for participatory design). Design, by its dictionary definition, is about making drawings or plans for something. Again, in simple terms, we’re talking about people making stuff together (with intent).

If we want to determine what is and isn’t co-design—in theory and practice—we need more specific definitions. When researching co-design in public policy, I developed a definition based on academic literature and practice knowledge. I defined co-design then as ‘a design-led process, involving creative and participatory principles and tools to engage different kinds of people and knowledge in public problem-solving’ (Blomkamp 2018).

Breaking down this definition, I singled out three key components of co-design, which I continue to use:

Process: An iterative, design-led approach oriented towards innovation. This might be represented as the Double Diamond or another design thinking/human-centred design or social/systems innovation process.

Principles: Participative, inclusive, respectful, iterative and outcomes-focused values—though I now use a slightly updated set of co-design principles.

Practice: Creative and tangible methods for telling, enacting and making. A great example is prototyping, which can take the form of telling a story, acting out a scenario, or making a model.

Co-design and its false friends

Like faux amis in language learning—words that look similar but have different meanings—co-design has several ‘false friends’ out there. These concepts sound similar and share some features with co-design, but they differ in important ways. Understanding these distinctions helps ensure we’re using the right approach for our context and being clear about what we’re offering.

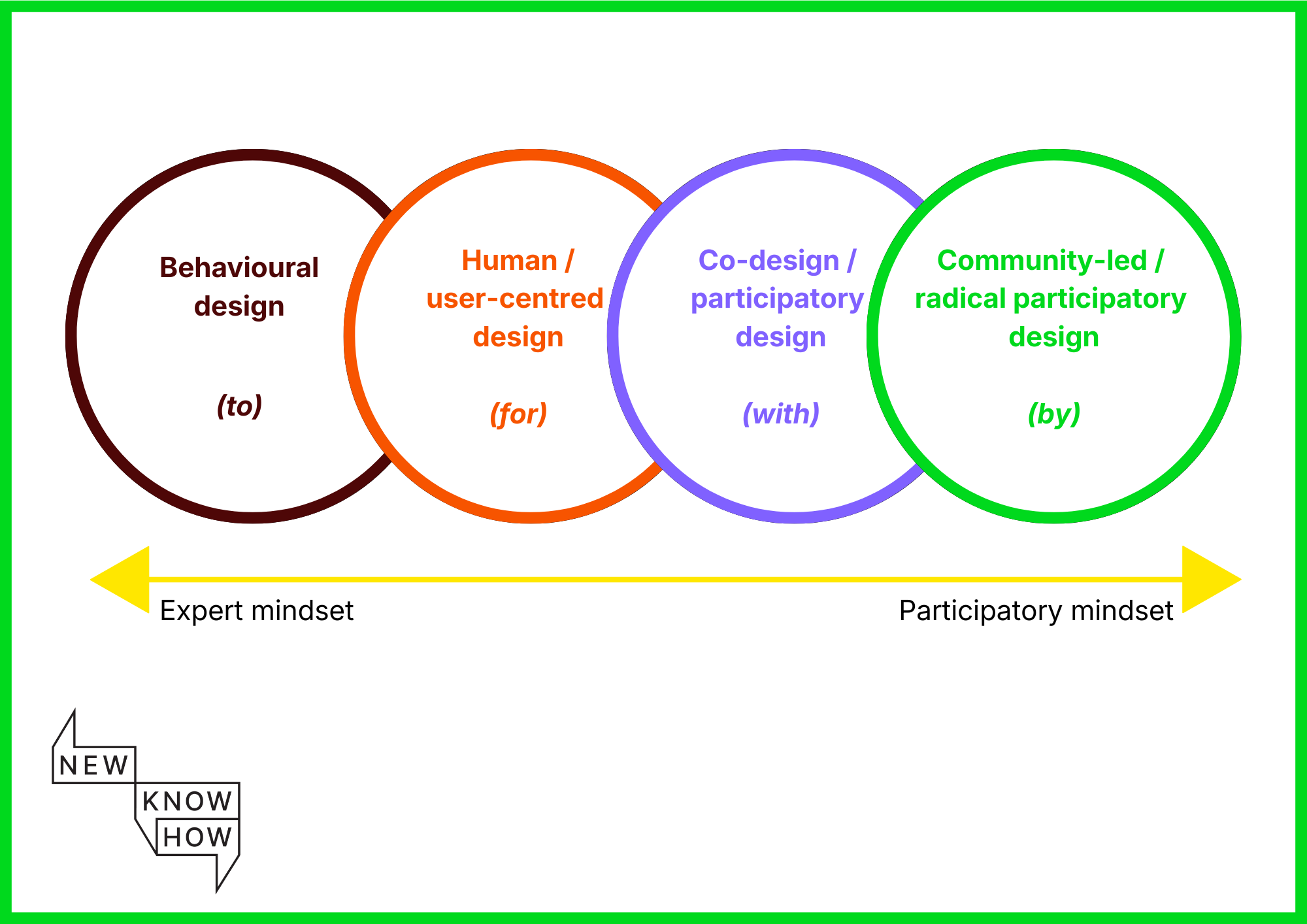

We can picture co-design on a spectrum of design participation, with ‘designing to’ based on an expert mindset at one end, to ‘designing by’ with a fully participatory mindset at the other.

Human-centred (or user-centered) design

False friendship: Both co-design and HCD/UCD involve understanding users’ (or consumers’/community members’) needs and designing solutions that are desirable, feasible and viable.

Key difference: Human-centred design is about designing for people, while co-design is about designing with them.

In practice: In human-centred design, professionals gather insights from ‘users’ but maintain control of the design process; people with lived experience are not necessarily active participants in generating meanings, ideas or actions.

Co-production

False friendship: Both of the ‘co’s involve collaboration and some power sharing; both can involve partnership between people with lived and professional experience in implementing ideas.

Key difference: Co-production focuses on partnership in service delivery (or in knowledge production, in academic contexts), while co-design emphasises collaborative creativity in the research/discovery and design/development process.

In practice: Co-production may encompass the whole policy process or just implementation (or knowledge production), but doesn’t necessarily involve a design-led process or creative methods.

Community engagement

False friendship: Both involve working with community members.

Key difference: Community engagement covers a broad range of approaches and in practice is often consultative rather than collaborative.

In practice: Standard community engagement approaches don’t follow a design-led process, use creative methods, or lead to innovation.

Consultation

False friendship: Both involve seeking input from relevant people.

Key difference: Consultation typically gathers feedback on pre-defined options, while co-design actively involves people in generating and developing options.

In practice: In consultation, the power to make decisions remains firmly with the organisation, whereas co-design involves meaningful power-sharing.*

*Side note: there are plenty of instances where power cannot be meaningfully shared, and consultation is a perfectly appropriate approach. Not everything can or should be co-designed.

The distinguishing feature of co-design is the active involvement of people with lived experience alongside professionals, or those with learned experience, as partners throughout the creative process. Community members are not just consulted but are genuinely collaborating in developing understanding and options for action.

Shades of co-design

Co-design doesn’t need to be a binary ‘you do it or you don’t’ proposition. There are different shades or levels that can be applied depending on context:

Full co-design process: A comprehensive approach involving people with a relevant range of lived and professional expertise throughout the entire process, from problem definition to implementation.

Co-design phase(s): Specific stage(s) where people with relevant lived and professional expertise collaborate on particular aspects of a project, e.g. through a series of facilitated workshops.

Co-design elements: Incorporating collaborative design principles at certain moments within a broader process that is not necessarily collaborative, creative or innovative, e.g. taking a more inclusive, playful and participatory approach in meetings about project management or research.

The appropriate shade of co-design depends on several factors, including:

The scope and complexity of what’s being designed

Available time and resources

The capabilities and authorising environment of the organisation

The circumstances and needs of potential co-designers.

When to use co-design

Co-design is particularly valuable when:

Different perspectives are needed to understand a complex issue or ‘wicked problem’

There are different views on what the problem is or what the solutions could be

Building ownership and buy-in from stakeholders is important for successful implementation

You’re working on issues that affect people’s lives directly and want to ensure what you create or implement meets their needs

Traditional approaches have failed to address persistent problems.

When co-design might not be the right approach

Co-design may not be appropriate when:

The solution is already clearly specified with little room for change

There’s no openness to doing something differently

You lack time or resources for meaningful participation

You lack skills or resources for appropriate facilitation

You can’t involve people with lived experience of the issue

You can’t involve people with professional experience in the sector

You’re responding to a crisis requiring immediate action.

Key considerations before starting co-design

Before embarking on a co-design process, consider the following:

Purpose and scope

Be clear about what you’re trying to achieve and what is (and isn’t) open to co-design. It’s a myth that co-design requires a blank slate or totally blue skies approach. All projects have constraints. Being transparent about these from the beginning is critical to building trust and enabling creativity.

Resources

Assess whether you have:

Time for learning and iteration

Budget for facilitation and participant compensation

Flexibility in project plans.

If you don’t, maybe you should just aim for some solid consultation.

Capabilities

Evaluate co-design capabilities at three levels:

Individual skills and knowledge

Team practices

Organisational conditions and support

Many co-design efforts face challenges not because of individual skills but due to organisational constraints or lack of an authorising environment.

Context and history

Be aware of the history of engagement with the communities you’re working with, especially when collaborating with groups who may have had negative experiences with previous “participatory” processes. This is particularly important when working on First Nations issues or with other historically marginalised communities.

Avoiding co-washing

“Co-washing” occurs when organisations use co-design terminology without genuinely sharing power, drawing on creativity or facilitation, or meaningfully involving people in the process. To avoid this, ask yourself:

Is there real ‘co’ happening—actual widening of participation and meaningful collaboration?

Is there ‘design’ happening—are you using creative methods and/or following a design process?

Example in practice

An example co-design project I like to share is Behind the Wheel from Aotearoa (New Zealand). Government agencies focused on the community of Māngere (in South Auckland) to address unlicensed driving among young people—an issue affecting not just road safety but also employment, social and cultural opportunities. After a wide range of community members participated as peer researchers in the discovery process, a co-design group comprising young drivers, whānau (family members), community leaders, professionals and ‘creative provocateurs’ explored the issues and opportunities, making decisions around problem definition and ideas to be tested and implemented.

Community members were not merely consulted. They actively shaped the programme’s design and delivery, with some co-designers becoming change agents in their own families and communities. The resulting Behind the Wheel campaign successfully increased knowledge about licensing requirements and enabled families to follow the rules. Most significantly, when government funding ended, a local community organisation chose to continue the programme independently, recognising its value in bringing the community together and supporting young people—a powerful indicator of genuine community ownership achieved through authentic co-design.

Research shows how co-design activities can create spaces for imagining possibilities that might otherwise remain unexpressed. For example, some recent action research by Rachel Goff and colleagues demonstrated that co-design methods enabled women who had experienced homelessness to imagine and design housing and support services that would provide the feeling of stability, constancy and control that comes from having safe, affordable housing.

The women used visual methods, storytelling and prototyping to express their needs for security, privacy and community. These methods allowed them to share their expertise from lived experience and collaboratively develop housing models that reflected their priorities. The researchers noted how trust-building and creating psychologically safe spaces were essential to this process.

Final words

Whether you call it co-design, participatory design, or some other term, the essence of this approach is about widening access and enabling people to meaningfully participate in creating better results for all.

As I often emphasise, it all comes back to purpose. When making decisions about whether and how to use co-design, getting clear on why you’re doing it and what difference you’re trying to make will guide you toward the right approach.

By focusing on purpose rather than getting caught up in terminology debates, we can develop more inclusive, effective and sustainable responses to complex problems.

Keen to put these ideas into practice? Join one of our online cohort-based learning programs, such as Fundamentals of Co-Design – or get expert guidance and support on how you’re applying co-design through project coaching or individual mentoring.

This blog draws on my academic writing (particularly The Promise of Co-Design for Public Policy), more recent experience delivering Fundamentals of Co-Design training, and conversations on podcasts such as It Depends.

Thanks to everyone who has asked good questions over the years and pushed me to get clearer on my terminology.